Finally it came. The Ford had been monotonously patrolling off the Postillion Islands, at the southern entrance to Macassar Straits. We knew the Japs were coming. Borneo was next on their timetable after Manila and Davao. The planes of Patwing Ten had been sending reports of a growing Jap Force at Davao. This Force could have only one objective, Balikpapan, on the eastern coast of Borneo, fronting on Macassar Straits.

Our orders were clear, "Make a night attack on a Japanese Force heading for Balikpapan." Reconnaissance reports began to trickle in. The job was going to be tough. "Twenty transports, twelve destroyers, several cruisers." We figured that the Japs would have so many ships there they'd never notice us. That's exactly what happened.

We started up the straits that evening, timing our approach to arrive off Balikpapan at about 02:00. The seas were extremely heavy; we had to make 27 knots to get there. The result was something even old William Cramp would have shuddered at. He built well when he put those old boats together. They bucked mountainous seas that threatened every minute to strip the bridges right off their hulls. I could only moan every time my guns went under green water. I was sure they'd never fire when the time came.

The long run up the Straits gave us time to organize for battle. We weren't much, but we were full of fight, and what's more, we were the "Fighting Fifty-ninth." Destroyer Division Fifty-Nine was under the command of Commander P. H. Talbot, U.S. Navy, and was composed of the John D. Ford, flagship, the Pope, the Parrott, and the Paul Jones in column in that order. We'd made many a practice night torpedo attack, but never one with the chips down. In fact, we were to make the first one ever made. I remember running over in my mind the lofty War College comments on the expected life of a destroyer in a night action. I couldn't remember if it was measured in seconds or minutes, but I knew it wasn't much of either. Our crews were well trained, tough, and eager for action. Our officers were the same, and as experienced as any in the peace-time Navy. We were confident, but we all made preparations just the same. The charts showed 300 miles of trackless jungle south of Balikpapan. I knew we'd have a long walk south if any of us were fortunate enough to survive and get ashore if we were sunk. I sewed a box full of fish hooks, twine, razor blades, quinine pills, and Dutch money in my life jacket and tied a pocket compass and knife on my pistol belt. After checking over my gun firing circuits as best I could between submergings and giving last-minute instructions to my gun crews, I felt I was ready for anything. My men were spoiling for a fight. I didn't have to tell then what to do, just when. They were about to take part in the first American naval engagement in the East since Dewey fought at Manila Bay, and they were proud of it.

I've always wondered how a person felt before battle. I still don't know. I fell asleep, os as near to sleep as you can get on a four-stacker that is making 27 knots in a rough sea. When the General Alarm awakened me at 23:00, the sea had calmed considerably, and as we passed up the straits in the lee of Celebes, the sea was almost calm.

Again I checked my guns, mustered my crews, passed last-minute instructions, and then reported ready to the bridge. I had plenty of time to think now. As my eyes became accustomed to the darkness I was able to make out our division mates astern. Down on deck the repair party was assembling its gear, the cooks were passing out cold rations, and the torpedo tube mount crews and gun crews were making last minute inspections.

We settled down to that last-minute wait, familiar to any athlete. That's the only way I can describe it, just like that gone feeling just before the kick off. For more than an hour we plunged on through the night, alert, ready, hopeful. Shortly before midnight the spotter in the foretop sighted an intermittently flashing light on the starboard bow. For a moment I thought it was a searchlight, but soon we made it out as flames from a burning ship. Its position showed it to be near a part of a Jap convoy reportedly bombed by our air force that afternoon. In half an hour we had left it astern, burning at a monument to the accuracy of some bombardier.

At 02:00 we came abreast of Balikpapan. The loom of gigantic fires became visible. The Dutch, we knew, were busy destroying everything burnable to deny it to the Japs. We couldn't smell burning oil 20 miles at sea. Using these fires as beacons, we turned west and set a course to the area just north of Balikpapan and its mine fields, where we suspected the Japs would attempt to land. At 02:45 I saw my first Japanese ship. I can't describe the feeling it gave me. I could remember the hours I'd spent studying silhouette all right, but not a picture--a big, black, ugly ship. We passed it so close and so fast that neither of us could take any action. Our plan was to fire our torpedoes as long as they lasted and then, and only then, to open up with our guns. That way we could conceal our presence as long as possible. Consequently, we couldn't fire our guns at this ship, and couldn't train our torpedo tubes fast enough to bring them to bear on him.

We didn't have long to wait for more game. A whole division of Jap destroyers burst out of the gloom and oil smoke on our port bow and steamed rapidly across in front of us and off into the darkness to starboard. Again we kept quiet and attempted to avoid them. Our objective was something far more important, the troop and supply laden transports farther inshore. I don't know why these destroyers didn't see us. Possibly several of their own destroyers were patrolling in the vicinity and they mistook us for their own forces. Maybe that was why the first ship we sighted had first fired on us.

Suddenly we found ourselves right in the midst of the Jap transports. Down on the bridge I could hear Captain Cooper saying "action port, action port," and Lieutenant Slaughter, the torpedo officer, giving quick orders to his torpedo battery. Back aft the tube mounts swung to follow his director. "Fire one," he said. "fire one," repeated his telephone talker. Then came the peculiar combination of a muffled explosion, a whine, a swish, and a splash, that follows the firing of a torpedo. I watched the torpedo come to the surface once and then dive again as it steadied on its run. Astern, the Pope, Paul Jones, and Parrott were carefully picking targets and firing. We fired our second torpedo. So did the ships astern. My talker was calmly counting off seconds as our first torpedo ran toward its target. "Mark," he shouted, as the time came for it to hit. Seconds passed. Nothing happened. We knew our first had missed. Then came a blinding, ear-shattering explosion. One of our torpedoes had hit. The explosion of a torpedo at night. at close range is an awe-inspiring sight. The blast is terrific, blinding; then comes the concussion wave, which leaves you gasping for breath. It is seconds before your dazed eyes can see anything at all.

Close on the heels of the first close range hit came other hits. The crippled ships began to list and sink. We reversed course and ran through the convoy again, firing torpedoes on both sides as transports loomed out of the dark. By now there were only three of us, the Paul Jones having lost us as we came around the last turn. At one time I could count five sinking ships. A third time we reversed course and ran through the demoralized convoy. Once we had to veer to port to avoid a sinking transport. The water was covered with swimming Japs. Our wash overturned several lifeboats loaded with Japs. Other ships looked as if they were covered with flies. Jap soldiers were clambering down their sides in panic. It was becoming difficult to keep from firing at transports that had already been torpedoed. Again we turned for another run through the convoy. So far I believed the Japs had not discovered that we were in their midst, attributing the torpedoes to submarines and believing we were their own destroyers.

Down on the bridge I heard "Fire ten." Just two torpedoes left. Now only the Pope was left astern of us. We fired our last two torpedoes at a group of three transports. Now I knew the stage was mine. Many a time I had fired at target rafts, but this was the real thing. "Commence firing." rang in my earphones. I was ready but how different this was from peace time firings! I could still remember the sonorous arguments of the publications I had studied at the Naval Academy over the relative effectiveness of searchlights and star shells. I didn't use either, nor did we use any of the complicated fire-control apparatus installed. This was draw shooting at its best. As targets loomed out of the dark at ranges of 500 to 1,500 yards we trained on and let go a salvo or two, sights set at their lower limits, using the illumination furnished by burning ships. Finally we sighted a transport far enough away to let us get in three salvos before we had passed it. The projectile explosions were tremendous. Deck plates and debris flew in all directions. When we last saw her she was on end, slipping slowly under. We had sunk the first ship to be sunk by American gunfire since Manila Bay! I only had a minute to reflect on that fact because a transport began firing at us. I turned my guns on her, but before we could silence her a shell had hit us aft. Flames grew and spread around the area. Over the telephone I could hear a torpedoman describing the damage--"four men wounded, the after deckhouse wrecked, ammunition burning." Thirty seconds later the burning ammunition had been thrown over the side, the wounded cared for, and the gun crew was firing again.

By now the Pope had also lost us, and we were fighting alone. One more transport we mauled badly, then there was nothing left to shoot at. On the bridge I heard our Division Commander give the order to withdraw. Back aft the blowers began to whine even louder as the Chief Engineer squeezed the last ounce of speed out of the old boat. Later I learned we were making almost 32 knots, faster than the Ford had gone since her trials. In the east the sky was growing uncomfortably bright. Astern of us the sky was also bright, but from the fires of burning ships.

For almost 30 minutes we ran south before dawn came. All hands strained their eyes astern for signs of pursuit that we thought inevitable. We could see none. The only ships in sight were three familiar shapes on the port bow that we knew to be the Parrott, Paul Jones, and Pope. Proudly they fell in astern of us, and we sped south together. Down on the bridge a flag hoist whipped out smartly. "Well done," it said.

All that morning we kept a wary eye cocked astern and overhead, but the Japs must have been licking their wounds, for we never saw a Jap. Our crew ate in shifts, refusing to get more than 10 feet from their guns. Only when we started in the mine fields off Soerabaja next day did they relax and drop off to sleep on deck.

At noon we tied up at Soerabaja with barely enough fuel to make the dock. On the way in we had put a canvas patch over the hole in our after deckhouse and had cleaned up the ship as best we could. The Dutch met us in grand style, and Admiral Hart came aboard to inspect us. The Dutch provided men to help us fuel and provision ship. That done, every man in the crew slept 16 hours . . .

(Editor's Note: Unhappily, when the facts were known six years later, it was ascertained through Japanese records that the three American tin-cans had sunk only 4 transports out of a possible 12, and only one patrol craft.)

For almost 30 minutes we ran south before dawn came. All hands strained their eyes astern for signs of pursuit that we thought inevitable. We could see none. The only ships in sight were three familiar shapes on the port bow that we knew to be the Parrott, Paul Jones, and Pope. Proudly they fell in astern of us, and we sped south together. Down on the bridge a flag hoist whipped out smartly. "Well done," it said.

All that morning we kept a wary eye cocked astern and overhead, but the Japs must have been licking their wounds, for we never saw a Jap. Our crew ate in shifts, refusing to get more than 10 feet from their guns. Only when we started in the mine fields off Soerabaja next day did they relax and drop off to sleep on deck.

At noon we tied up at Soerabaja with barely enough fuel to make the dock. On the way in we had put a canvas patch over the hole in our after deckhouse and had cleaned up the ship as best we could. The Dutch met us in grand style, and Admiral Hart came aboard to inspect us. The Dutch provided men to help us fuel and provision ship. That done, every man in the crew slept 16 hours . . .

(Editor's Note: Unhappily, when the facts were known six years later, it was ascertained through Japanese records that the three American tin-cans had sunk only 4 transports out of a possible 12, and only one patrol craft.)

--Rear Admiral William P. Mack

From: The United States Navy in World War II

Compiled and edited by: S.E. Smith

Part I: Chapter 8: Macassar Merry-Go-Round

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

| Thomas Charles Hart | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Connecticut | |

| In office February 15, 1945 – November 5, 1946 | |

| Preceded by | Francis T. Maloney |

| Succeeded by | Raymond E. Baldwin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 12, 1877 Davison, Michigan |

| Died | July 4, 1971 (aged 94) Sharon, Connecticut |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Caroline Brownson |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service | 1897–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | USS Chicago Submarine Division 2 Submarine Division 5 USS Mississippi Submarine Flotilla 3 Cruiser Division 6 United States Asiatic Fleet |

| Battles/wars | Spanish–American War |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Medal (2) |

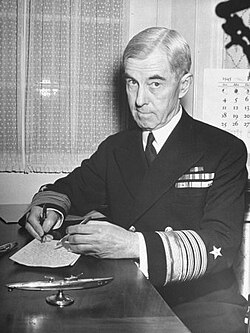

Thomas Charles Hart (June 12, 1877 – July 4, 1971) was an admiral of the United States Navy, whose service extended from the Spanish-American War through World War II. Following his retirement from the Navy, he served briefly as a United States Senator from Connecticut.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, coupled with nearly simultaneous assaults on British and Dutch possessions and the Philippines, catapulted the United States into World War II. On 8 December 1941 Hart proclaimed unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan,[6] and the Americans, with their Filipino allies, fought a delaying action in the Philippines, while a mixed American, British, Dutch, and Australian (ABDA) military structure under the command of General Hein ter Poorten was set up to operate fromJava in an attempt to hold the Japanese at the Malay Barrier.[1]

Given command of ABDA naval forces, Hart directed part of this defense into mid-February 1942 when he was replaced, for political reasons, by Admiral Helfrich of the Dutch Navy. By that point, it had become evident that the Japanese forces could not be stopped with the allied ships available at that time.[1]

He returned to the United States on 8 March 1942.[7] President Roosevelt presented Hart with a Gold Star in lieu of a secondDistinguished Service Medal in July 1942 for "His conduct of the operations of the Allied naval forces in the Southwest Pacific area during January and February, 1942, was characterized by unfailing judgment and sound decision, coupled with marked moral courage, in the face of discouraging surroundings and complex associations."

| United States Asiatic Fleet | |

|---|---|

The then-flagship of the Asiatic Fleet, the heavy cruiser Houston, at Tsingtao, China, on 4 July 1933. She flies the four-star pennant of the fleet's commander-in-chief, Admiral Montgomery M. Taylor and is dressed overall for Independence Day.

| |

| Active | 1902-1907; 1910-1942 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Naval fleet |

The United States Asiatic Fleet was a fleet of the United States Navy during much of the first half of the 20th century. Preceding the World War II era, until 1942, the fleet protected the Philippine Islands. Much of the fleet was destroyed that year, after which it was dissolved and incorporated into the 7th Fleet.

The fleet was created when its predecessor, the Asiatic Squadron, was upgraded to fleet status in 1902. In early 1907, the fleet was downgraded to became the First Squadron of the United States Pacific Fleet. However, on 28 January 1910, the ships of that squadron were again organized as the Asiatic Fleet. Thus constituted, the Asiatic Fleet, based in the Philippine Islands, was organizationally independent of the Pacific Fleet, which was based on theUnited States West Coast until it moved to Pearl Harbor in the Territory of Hawaii in 1940.

Although much smaller than any other U.S. Navy fleet and indeed far smaller than what any navy generally considers to be a fleet, the Asiatic Fleet from 1916 was commanded by one of only four four-star admirals authorized in the U.S. Navy at the time. This reflected the prestige of the position of Asiatic Fleet commander-in-chief, who generally was more powerful and influential with regard to the affairs of the United States in China than was the Americanminister, or later United States Ambassador, to China.[1]

On 25 July 1939,[3] Admiral Thomas C. Hart was appointed the commander-in-chief of the fleet. It was based at Cavite Naval Baseand Olongapo Naval Station on Luzon, with its headquarters at the Marsman Building in Manila. On 22 July 1941, the Mariveles Naval Base was completed and the Asiatic Fleet began to use it as well.

Hart had permission to withdraw to the Indian Ocean, in the event of war with Japan, at his discretion.

Hart's submarines, commanded by Commander, Submarines, Asiatic Fleet (COMSUBAF) Captain John E. Wilkes with six elderly "S"-class submarines (and submarine tender Canopus)[4] and seven Porpoises (in Submarine Squadron 5, SubRon 5),[5] In October 1941, 12 Salmons or Sargos—in Captain Stuart "Sunshine" Murray's Submarine Division 15 {SubDiv 15} and Captain Joseph A. Connolly's SubDiv 16, as SubRon 2—accompanied by the tender Holland, were added. Walter E. "Red" Doyle was assigned as Wilkes' relief.[6]Hart's defensive plan relied heavily on his submarines, which were believed to be "the most lethal arm of the insignificant Asiatic Fleet",[5] to interdict the Japanese and whittle down their forces prior to a landing, and to disrupt attempts at reinforcing after the landings took place.[7] When war began, Doyle's inexperience in Asian waters meant Wilkes remained de facto COMSUBAS.[6]

Problems were encountered almost from the beginning. No defensive minefields were laid.[8] Ineffective and unrealistic peace time training, inadequate (or nonexistent) defensive plans, poor deployments, and defective torpedoes combined to make submarine operations in defense of the Philippines a foregone conclusion.[8] No boats were placed in Lingayen Gulf, widely expected to be where the Japanese would land;[9] in the event, several S-boats, aggressively handled, scored successes there.[10] Nor were any boats off ports of Japanese-held Formosa, despite more than a week's warning of impending hostilities.[9] Successes were few in the early days of the war.[11]

Chinese Detachment[edit]

From 1901-1937, the United States military maintained a strong presence in China to maintain Far East trade interests and to pursue a permanent alliance with the Chinese Republic, after long diplomatic difficulties with the Chinese Empire. The relationship between the U.S. and China was mostly on-again off-again, with periods of both cordial diplomatic relations accompanied by times of severed relations and violent anti-United States protests.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Asiatic Fleet was based from China, and a classic image of the "China Sailor" developed, as a large number of U.S. Navy members would remain at postings in China for 10–12 years then retire and continue to live in the country. The classic film The Sand Pebbles is a dramatization on the life of the China Sailors.

The U.S. military also created several awards and decorations to recognize those personnel who had performed duty in China. TheChina Service Medal, China Campaign Medal, Yangtze Service Medal, and the China Relief Expedition Medal were all military medals which could be presented to those who had performed duty in China.

With the approach of World War II, the U.S. military in China was slowly withdrawn to protect other U.S. interests in the Pacific. With the rise of Communist China, there was no further U.S. military presence in mainland China, a status which continues to this day.

Early in November 1941, the Navy Department ordered Hart to withdraw the fleet's Marines and gunboats stationed in China. Five of the gunboats were moved to Manila, Wake was left with a skeleton crew as a radio base and was seized by the Japanese on 8 December and Tutuila was transferred to the Republic of China Navy under Lend-Lease.

The majority of the 4th Marine Regiment was stationed at Shanghai, and other detachments were at Peking (Beijing) and Tientsin(Tianjin). These troops were loaded onto two President class liners on 27–28 November (at either Shanghai or Chinwangtao(Qinghuangdao) and arrived in the Philippines on 30 November-1 December.

President Harrison returned to Chinwangtao, to move the remaining Marines, but was captured by the Japanese on 7 December. Those Marines which had reached the Philippines were tasked with defending the naval stations, particularly Mariveles Naval Base.

Minefields[edit]

Manila and Subic Bays (in support of the Harbor Defenses) were mined by the Asiatic Fleet, stationed in Manila Bay. These minefields were designed to stop all vessels, except for submarines and shallow-draft surface craft.

| William A. Glassford | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 6 June 1886 |

| Died | 30 July 1958 (aged 72) |

| Place of burial | Arlington National CemeteryArlington, Virginia |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Medal |

Vice Admiral William Alexander Glassford (6 June 1886 - 30 July 1958) was a United States Navy officer who served during World War II.

Glassford commanded naval forces of the United States Asiatic Fleet during the first month of World War II, and then relocated to Java in the Netherlands East Indies to combine his forces with the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command ("ABDA"). His most notable battle was the Naval Battle of Balikpapan, in which he led a U.S. task force in an attack against Japanese forces that had occupied the port of Balikpapan on Borneo. When Glassford'sflagships, the light cruisers USS Boise (CL-47) and USS Marblehead (CL-12), were disabled, he ordered his supporting destroyers to continue with the mission under Commander Paul H. Talbot. The attack came too late to prevent the capture of Balikpapan, and had little effect on the Japanese campaign to capture the resources of the Netherlands East Indies.

After the campaign, Glassford returned to the United States where he held a variety of positions in the 6th Naval District and the Eighth Fleet.

Class- Porpoise Class Submarine

Registry- SS-174

Launched- 21, May 1935

Shark, just after launch | |

| Career | |

|---|---|

| Name: | USS Shark |

| Builder: | Electric Boat Company, Groton, Connecticut[1] |

| Laid down: | 24 October 1933[1] |

| Launched: | 21 May 1935[1] |

| Commissioned: | 25 January 1936[1] |

| Fate: | Probably sunk by Japanese destroyerYamakaze east of Manado, 11 February 1942[2] |

| General characteristics | |

| Class & type: | Porpoise-class diesel-electricsubmarine[2] |

| Displacement: | 1,316 long tons (1,337 t) standard, surfaced[3] 1,968 long tons (2,000 t) submerged[3] |

| Length: | 287 ft (87 m) (waterline),[4] 298 ft (91 m) (overall)[5] |

| Beam: | 25 ft .75 in (7.6391 m)[3] |

| Draft: | 13 ft 9 in (4.19 m)[5] |

| Propulsion: |

(as built) 4 × Winton Model 16-201A16-cylinder two-cycle[6] diesel engines, 1,300 hp (970 kW) each,[7] drivingelectrical generators through reduction gears[2][8]

two shafts [2]2 × 120-cell Exide VL31B batteries[9] 4 × high-speed Elliott electric motors,[2] 3 × General Motors six-cylinder four-cycle 6-228 auxiliary diesels[7] (re-engined 1942) 4 × GM two-cycle Model 12-278A diesels, 1,200 hp (890 kW) each[7] 4,300 shp (3,200 kW) surfaced[2] 2,085 shp (1,555 kW) submerged[2] |

| Speed: | 19.5 kn (22.4 mph; 36.1 km/h) surfaced[3] 8.25 kn (9.49 mph; 15.28 km/h) submerged[3] |

| Range: | 6,000 nmi (6,900 mi; 11,000 km) at 10 kn (12 mph; 19 km/h) 21,000 nmi (24,000 mi; 39,000 km) at 10 kn (12 mph; 19 km/h) with fuel in the main ballast tanks[3] |

| Endurance: | 10 hours at 5 kn (5.8 mph; 9.3 km/h) 36 hours at minimum speed[3] |

| Test depth: | 250 ft (76 m)[3] |

| Capacity: | 85,946–86,675 US gal (325,340–328,100 l)[10] |

| Complement: | 5 officers, 49 enlisted[3] |

| Armament: | 6 × 21 in (530 mm) torpedo tubes (four forward, two aft, 16 torpedoes)[3] 1 × 4 in (100 mm)/50 cal deck gun[5] 2 × 0.30 in (7.6 mm) machine guns[11] |

USS Shark (SS-174) was a Porpoise-class submarine, the fifth ship of theUnited States Navy to be named for the shark. Her keel was laid down by theElectric Boat Company in Groton, Connecticut, on 24 October 1933. She waslaunched on 21 May 1935 (sponsored by Miss Ruth Ellen Lonergan, 12-year-old daughter of United States Senator Augustine Lonergan of Connecticut), and commissioned on 25 January 1936, Lieutenant C.J. Carter in command.

On 6 January 1942, Shark was almost hit with a torpedo from an Imperial Japanese Navy submarine. A few days later, she was ordered to Ambon Island, where an enemy invasion was expected. On 27 January, she was directed to join the submarines patrolling in Strait of Malacca, then to cover the passage east of Lifamatola and Bangka Strait. On 2 February, Sharkreported to her base at Soerabaja that she had been depth-charged 10 mi (16 km) off Tifore Island and had failed to sink a Japanese ship during atorpedo attack. Five days later, she reported chasing an empty cargo ship headed northwest, for which Admiral Wilkes upbraided her commanding officer.[12] No further messages were received from Shark. On 8 February, she was told to proceed to Makassar Strait and later was told to report information. Nothing was heard and, on 7 March, Shark was reported as presumed lost, the victim of unknown causes, the first American submarine lost to enemy anti-submarine warfare.[13] She was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 24 June.

Post-war, Japanese records showed numerous attacks on unidentified submarines in Shark's area at plausible times. At 01:37 on 11 February, for example, the Japanese destroyer Yamakaze opened fire with her 5 in (130 mm) guns and sank a surfaced submarine. Voices were heard in the water, but no attempt was made to rescue possible survivors.

| The Right Honourable The Earl Wavell GCB GCSI GCIE CMG MC PC | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sir Archibald Wavell in Field Marshal's uniform | |

| Viceroy and Governor-General of India | |

| In office 1 October 1943 – 21 February 1947 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill Clement Attlee |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Linlithgow |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Mountbatten of Burma |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 May 1883 Colchester, Essex, United Kingdom |

| Died | 24 May 1950 (aged 67) Westminster, London, United Kingdom |

| Relations | Married to Eugenie Marie Quirk, one son and three daughters |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | British Army |

| Years of service | 1901–1943 |

| Rank | Field Marshal |

| Commands | 6th Infantry Brigade 2nd Division British Troops Palestine and Trans-Jordan Southern Command Middle East Command GHQ India American-British-Dutch-Australian Command |

| Battles/wars | Second Boer War

First World War:

Second World War:

|

| Awards | GCB (4 March 1941)

GCSI (Aug/September 1943)

GCIE (Aug/September 1943) KCB (2 January 1939) CB (1 January 1935) CMG (1 January 1919) Military Cross (23 June 1915) Knight of the Order of St. John(4 January 1944) Order of St Stanislaus, 3rd class with Swords (Russia) Order of St. Vladimir (Russia) (1917) Croix de Guerre (Commandeur)(France) (1920) Commandeur, Légion d'honneur(France) (1920) Order of El Nahda, 2nd Class(Hejaz) (1920) Grand Cross, Order of George I with Swords (Greece) (1941) Virtuti Militari, 5th Class (Poland) (1941) War Cross, 1st Class (Greece) (1942) Commander, Order of the Seal of Solomon (Ethiopia) (1942) Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Orange Nassau(Netherlands) (1943) War Cross (Czechoslovakia) (1943) Legion of Merit, Chief Commander (USA) (1948) |

Field Marshal Archibald Percival Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell GCB GCSI GCIE CMG MC PC (5 May 1883 – 24 May 1950) was a senior commander in the British Army. He served in theSecond Boer War, the Bazar Valley Campaign and the Great War, during which he was wounded in the Second Battle of Ypres. He served in the Second World War, initially as Commander-in-Chief Middle East, in which role he led British forces to victory over theItalians in western Egypt and eastern Libya during Operation Compass in December 1940, only to be defeated by the German army in the Western Desert in April 1941. He served as Commander-in-Chief, India, from July 1941 until June 1943 (apart from a brief tour as Commander of ABDACOM) and then served as Viceroy of India until his retirement in February 1947.

Wavell once again had the misfortune of being placed in charge of an undermanned theatre which became a war zone when the Japanese declared war on the United Kingdom in December 1941. He was made Commander-in-Chief of ABDACOM (American-British-Dutch-Australian Command).[49]

Late at night on 10 February 1942, Wavell prepared to board a flying boat, to fly from Singapore to Java. He stepped out of a staff car, not noticing (because of his blind left eye) that it was parked at the edge of a pier. He broke two bones in his back when he fell, and this injury affected his temperament for some time.[50]

Class- Clemson Class Destroyer

Registry- DD-228

AG-119

Launched- 2, September 1920

| |

| Career (US) | |

|---|---|

| Namesake: | John Donaldson Ford |

| Builder: | William Cramp & Sons |

| Laid down: | 11 November 1919 |

| Launched: | 2 September 1920 |

| Commissioned: | 30 December 1920 |

| Decommissioned: | 2 November 1945 |

| Struck: | 16 November 1945 |

| Honours and awards: | John D Ford received a Presidential Unit Citation (specifically honoring her "extraordinary heroism in action during the Java Campaign, 23 January - 2 March 1942) and four battle stars for her World War II service |

| Fate: | sold for scrap 5 October 1947 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class & type: | Clemson-class destroyer |

| Displacement: | 1,190 tons |

| Length: | 314 feet 5 inches (95.83 m) |

| Beam: | 31 feet 9 inches (9.68 m) |

| Draft: | 9 feet 3 inches (2.82 m) |

| Propulsion: | 26,500 shp (20 W); geared turbines, 2 screws |

| Speed: | 35 knots (65 km/h) |

| Complement: | 101 officers and enlisted |

| Armament: | 4 x 4"/50 (102/50 mm), 1 x 3"/25 (76/25 mm) AA, 2 x .30 (7.62 mm) cal MG., 12 x 21" (533 mm) torpedo tubes. |

USS John D. Ford (DD-228/AG-119) was a Clemson-class destroyer in theUnited States Navy during World War II. She was named for Rear AdmiralJohn Donaldson Ford.

John D. Ford was laid down 11 November 1919 and launched 2 September 1920 from William Cramp & Sons; sponsored by Miss F. Faith Ford, daughter of Rear Admiral Ford; and commissioned as Ford 30 December 1920,Lieutenant, junior grade L. T. Forbes in temporary command.

[edit]

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor 7 December 1941, John D. Ford readied for action at Cavite as a unit of DesDiv 59. Undamaged by the destructive Japanese air raid on Manila Bay 10 December, she sailed southward the same day to patrol the Sulu Sea andMakassar Strait with Task Force 6. She remained in Makassar Strait until 23 December, then she steamed from Balikpapan, Borneo, to Surabaya, Java, arriving the 24th.

As the Japanese pressed southward through the Philippines and into Indonesia, the Allies could hardly hope to contain the Japanese offensive in the East Indies. With too few ships and practically no air support they strove to harass the Japanese forces in an attempt to delay their advance, and to prevent the invasion of Australia. Anxious to strike back at the Japanese, Ford departed Surabaya 11 January 1942 for Kupang, Timor, where she arrived on the 18th to join a destroyer striking force. Two days later the force sailed for Balikpapanto conduct a surprise torpedo attack on Japanese shipping. Arriving off Balikpapan during mid watch 24 January, the four destroyers launched a raid through the Japanese transports while Japanese destroyers steamed about Makassar Strait in search of reported American submarines. For over an hour the destroyers fired torpedoes and shells at the astonished enemy. Before retiring from the first surface action in the Pacific war, they sank four Japanese ships, one a victim of John D. Ford's torpedoes. The striking force arrived Surabaya 25 January.

Class-Clemson Class Destroyer

Registry-DD-225

Launched-23, March 1920

| |

| Career (US) | |

|---|---|

| Namesake: | John Pope |

| Builder: | William Cramp and Sons |

| Laid down: | 9 September 1919 |

| Launched: | 23 March 1920 |

| Commissioned: | 27 October 1920 |

| Struck: | 8 May 1942 |

| Fate: | sunk in battle, 1 March 1942 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class & type: | Clemson-class destroyer |

| Displacement: | 1,190 tons |

| Length: | 314 feet 5 inches (95.83 m) |

| Beam: | 31 feet 9 inches (9.68 m) |

| Draft: | 9 feet 3 inches (2.82 m) |

| Propulsion: | 26,500 shp (20 MW); geared turbines, 2 screws |

| Speed: | 35 knots (65 km/h) |

| Complement: | 101 officers and enlisted |

| Armament: | 4 x 4-inch, 1 x 3-inch, 2 .30 cal, 12 x 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes |

| Aircraft carried: | none |

USS Pope (DD-225) was a Clemson-class destroyer in the United States Navy that served during World War II. She was the first ship named for John Pope.

Pope was laid down 9 September 1919 and launched 23 March 1920 from William Cramp and Sons; sponsored by Mrs. William S. Benson; and commissioned 27 October 1920 at Philadelphia, Commander Richard S. Galloway in command.

Pope was heavily engaged in fighting in the Dutch East Indies in the early days of World War II. On 9 January 1942 Pope was one of five destroyers in an escort composed of the cruisers USS Boise (CL-47) and USS Marblehead (CL-12), with the other destroyersUSS Stewart (DD-224), USS Bulmer (DD-222), USS Parrott (DD-218), and USS Barker (DD-213) departing from Darwin to Surabaya escorting the transport Bloemfontein.[1] That transport had been part of the Pensacola Convoy and had left Brisbane 30 December 1941 with Army reinforcements composed of the 26th Field Artillery Brigade and Headquarters Battery, the 1st Battalion, 131st Field Artillery and supplies from that convoy destined for Java.

During the Battle of Balikpapan she made close-quarter torpedo and gun attacks which helped delay Japanese landings at Balikpapan and later in the Battle of Badung Strait she impeded the invasion of the island of Bali.

Class-Clemson Class Destroyer

Registry-DD-218

Launched-25, November 1919

| |

| Career (US) | |

|---|---|

| Namesake: | George Fountain Parrott |

| Builder: | William Cramp & Sons Shipbuilding & Engine Company |

| Laid down: | 23 July 1919 |

| Launched: | 25 November 1919 |

| Commissioned: | 11 May 1920 |

| Decommissioned: | 14 June 1944 |

| Struck: | 18 July 1944 |

| Fate: | sold for scrapping 5 April 1947 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class & type: | Clemson-class destroyer |

| Displacement: | 1,190 tons |

| Length: | 314 feet 4 inches (95.81 m) |

| Beam: | 30 feet 8 inches (9.35 m) |

| Draft: | 13 feet 6 inches (4.11 m) |

| Propulsion: | 26,500 shp (20 MW); geared turbines, 2 screws |

| Speed: | 35 knots (65 km/h) |

| Complement: | 157 officers and enlisted |

| Armament: | 4 x 4" (102 mm), 4 x 21" (533 mm) TT. |

USS Parrott (DD-218) was a Clemson-class destroyer in the United States Navy during World War II. She was the second ship named for George Fountain Parrott.

Parrott was laid down 23 July 1919 by and launched 25 November fromWilliam Cramp & Sons Shipbuilding & Engine Company; sponsored by Miss Julia B. Parrott; and commissioned 11 May 1920, Lieutenant Commander W. C. Wickham in command.

In Cavite Navy Yard, Parrott spent the first two months of 1941 having anti-mine and sound detection gear installed, after which, she trained with destroyers and submarines. She assumed duties as off-shore sound patrol picket at the entrance to Manila Bay on 6 October, and late in November joined Task Force 5 at Tarakan, Borneo, Netherlands East Indies. The Task Force was still operating in this area when hostilities began.

When the Philippines fell to the Japanese, the Asiatic Fleet moved south and operated under a unified American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDA) from a base at Surabaya, Java. On 9 January 1942 Parrott was one of five destroyers in an escort composed of the cruisers USS Boise (CL-47) and USS Marblehead (CL-12), with the other destroyers USS Stewart (DD-224),USS Bulmer (DD-222), USS Pope (DD-225), and USS Barker (DD-213) departing from Darwin to Surabaya escorting the transportBloemfontein.[1] That transport had been part of the Pensacola Convoy and had left Brisbane 30 December 1941 with Army reinforcements composed of the 26th Field Artillery Brigade and Headquarters Battery, the 1st Battalion, 131st Field Artillery and supplies from that convoy destined for Java.[2]

After dark, on 23 January 1942, Parrott, with John D. Ford, Pope and Paul Jones, entered Balikpapan Bay where, lying at anchor, were 16 Japanese transports and three 750-ton torpedo boats, guarded by a Japanese Destroyer Squadron. The Allied ships fired several patterns of torpedoes and saw four enemy transports and one torpedo boat sink as the Japanese destroyers searched in the strait for non-existent submarines.

Class: Clemson Class Destroyer

Registry: DD-230

Launched: 30, September 1920

| |

| Career (US) | |

|---|---|

| Namesake: | John Paul Jones |

| Builder: | William Cramp and Sons |

| Laid down: | 23 December 1919 |

| Launched: | 30 September 1920 |

| Commissioned: | 19 April 1921 |

| Decommissioned: | 5 November 1945 |

| Struck: | 28 November 1945 |

| Fate: | Sold for scrap on 5 October 1947 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class & type: | Clemson-class destroyer |

| Displacement: | 1,215 tons |

| Length: | 314 feet 4 inches (95.81 m) |

| Beam: | 30 feet 8 inches (9.35 m) |

| Draft: | 9 feet 4 inches (2.84 m) |

| Propulsion: | 26,500 shp (20 MW); geared turbines, 2 screws |

| Speed: | 35 knots (65 km/h) |

| Complement: | 145 officers and enlisted |

| Armament: | 4 x 4" (102 mm), 1 x 3" (76 mm), 6 x 21" (533 mm) tt. |

USS Paul Jones (DD-230/AG–120) was a Clemson-class destroyer in theUnited States Navy during World War II. It was the third ship named for John Paul Jones.

Paul Jones was laid down 23 December 1919 and launched 30 September 1920 from William Cramp & Sons; sponsored by Miss Ethel Bagley; and commissioned 19 April 1921.

As flagship of Destroyer Squadron 29, Asiatic Fleet, she received the news of the attack on Pearl Harbor 8 December 1941, at Tarakan, Borneo, and immediately prepared for action. She got underway with Marblehead, Stewart,Barker, and Parrott for Makassar Strait and for the remainder of December acted as picket boat in the vicinity of Lombok Strait and Soerabaja Harbor,Java.

Her first war orders were to contact Dutch] Naval Units for instructions pertaining to the search for a submarine in the Java Sea, which was reported to have sunk the Dutch vessel Langkoems, contact her survivors on Bawean Island and check the waters for additional survivors. Paul Jones was unable to make contact with the submarine, but rescued Dutch crewmen. On 9 January 1942, after a Japanese submarine had sunk a second Dutch merchantman, Paul Jones saved 101 men from drifting life-boats. With Van Ghent, she salvaged the abandoned U.S. Army cargo vessel Liberty, 12 January, and towed it safely to Bali. She joined a raiding group consisting of three other destroyers: John D. Ford, Pope, and Parrott, along with cruisersMarblehead and Boise, hoping to intercept a large enemy convoy heading southward toward Balikpapan. Boise retired early from the group because of a grounding mishap and Marblehead developed a faulty turbine forcing her to reduce speed and remain behind the destroyers to act as cover for withdrawal. The destroyers engaged the Japanese convoy and its screening warships the night of 23/24 January. Despite overwhelming odds, they came out of the fracas with only minor damage to John D. Ford. The enemy suffered losses from the torpedo attacks launched by the destroyers as they raced back and forth through the transport formation.

On 5 February Paul Jones rendezvoused with Tidore off Sumbawa Island to escort her to Timor. Shortly after they joined up, they were attacked by three separate groups of Japanese bombers. Paul Jones successfully dodged approximately 20 bombs, but Tidore was aground and a total loss. Fifteen crew members were picked up from a life boat, five were taken off the stricken vessel, and six more were gathered from the beaches. Paul Jones then steamed on to Java.

The American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDA) commenced sweeps 24 February in search of enemy surface forces which might be attempting to make landings in the Java area, and to give what opposition they could to the Japanese advance. They encountered a Japanese covering force in the afternoon of 27 February and the Allies opened fire, beginning the Battle of the Java Sea. By 1821, Paul Jones had expended her torpedoes. Dangerously low on fuel, she retreated to Soerabaja. The next morning Paul Jones and three other U.S. destroyers escaped encirclement by Japanese forces closing on all sides of Java, by hugging close to the shore line and laying smoke at high speed when sighted in the Bali Strait. Paul Jones and John D. Ford later escorted Black Hawk on to Fremantle, Australia, arriving 4 March.

Class: Omaha Class Light Cruiser

Registry: CL-12

Launched: 9, October 1923

USS Marblehead (CL-12) | |

| Career | |

|---|---|

| Name: | USS Marblehead |

| Builder: | William Cramp and Sons,Philadelphia |

| Laid down: | 4 August 1920 |

| Launched: | 9 October 1923 |

| Commissioned: | 8 September 1924 |

| Decommissioned: | 1 November 1945 |

| Struck: | 28 November 1945 |

| Fate: | Scrapped in 1946 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class & type: | Omaha-class cruiser |

| Displacement: | 7,050 long tons (7,160 t) |

| Length: | 555 ft 6 in (169.32 m) |

| Beam: | 55 ft 4 in (16.87 m) |

| Draft: | 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m) |

| Speed: | 34 kn (39 mph; 63 km/h) |

| Complement: | 458 officers and enlisted |

| Armament: | 12 × 6 in (150 mm)/53 cal guns (2x2, 8x1), 4 × 3 in (76 mm)/50 cal guns (4x1), 6 × 21 in (530 mm) torpedo tubes |

| Service record | |

| Operations: | World War II • Battle of Makassar Strait • Operation Dragoon |

| Awards: | 2 battle stars (World War II) |

USS Marblehead (CL-12) was an Omaha-class light cruiser of the United States Navy. She was the third Navy ship named for the town of Marblehead, Massachusetts.

Marblehead was laid down on 4 August 1920 by William Cramp and Sons,Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; launched on 9 October 1923; sponsored by Mrs. Joseph Evans; and commissioned on 8 September 1924, Captain Chauncey Shackford in command.

"About on 24 November 1941," her war diary reported, "the Commander–in–Chief, U.S. Asiatic Fleet sensed that the relations between the United States and Japan had reached such a critical state that movement of men–of–war...was indicated." The next day,Marblehead, with Task Force 5 (TF 5), departed Manila Bay for seemingly "routine weekly operations." She anchored at Tarakan,Borneo on 29 November and waited for further instructions. On 8 December (7 December in the United States) she received the message "Japan started hostilities; govern yourselves accordingly."

Battle of Makassar Strait, 1942[edit]

Marblehead and other American warships then joined with those of the Royal Netherlands Navy and the Royal Australian Navy to patrol the waters surrounding the Netherlands East Indies and to screen Allied shipping moving south from the Philippines. On the night of 24 January 1942, Marbleheadcovered the withdrawal of a force of Dutch and American warships after they had attacked, with devastating effect, an enemy convoy off Balikpapan. Six days later, in an attempt to repeat this success, the force departed Surabaja,Java, to intercept an enemy convoy concentration at Kendari. The Japanese convoy, however, sailed soon after, and the Allied force changed course, anchoring in Bunda Roads on 2 February. On the 4th, the ships steamed out of Bunda Roads and headed for another Japanese convoy sighted at the southern entrance to the Makassar Straits. At 0949, 36 enemy bombers were sighted closing in on the formation from the east.

In the ensuing Battle of Makassar Strait, Marblehead successfully maneuvered through three attacks. After the third an enemy plane spiraled toward the cruiser, but her gunners splashed it. The next minute a fourth wave of seven bombers released bombs at Marblehead. Two were direct hits and a third a near miss close aboard the port bow causing severe underwater damage. Fires swept the ship as she listed to starboard and began to settle by the bow. Her rudder jammed,Marblehead, continuing to steam at full speed, circled to port her gunners kept firing, while damage control crews fought the fires and helped the wounded. By 1100, the fires were under control. Before noon the enemy planes departed, leaving the damaged cruiser with 15 dead or mortally wounded and 84 seriously injured.

Marblehead's engineers soon released the rudder angle to 9° left, and at 1255, she retired to Tjilatjap, steering by working the engines at varying speeds. She made Tjilatjap with a forward draft of 30 ft (9 m), aft 22 ft (7 m). Unable to be docked there, her worst leaks were repaired and she put to sea again on the 13th, beginning a voyage of more than 9,000 mi (14,000 km) in search of complete repairs.

No comments:

Post a Comment