Empress Augusta Bay

By: Theodore Roscoe

When word reached Admiral Kona at Truk that the Americans had dared to put foot on Bougainville, he radioed instructions to strike the interloper and strike hard.

|

| Admiral Sentarō Ōmori |

Rabaul’s air strength was mustered, and with air power to back him up, Rear Admiral Sentaro Omari set out from Rabaul late in the afternoon of November 1 with a bloodthirsty surface force. Mission: to blast the Americans at Cape Torokina.  |

Myōkō in Singapore at the end of World War II.

Submarines I-501 and I-502 are tied up alongside. |

In Omari’s force were heavy cruisers Myoko and Haguro, light cruisers Sendai and Agano, and six destroyers. Five troop-carrying assault transports sortied with the force, intending to land a thousand soldiers on the Torokina beaches to give battle to the U.S. Marines. But these APD’s were late for the rendezvous, and after an American sub was sighted near St. George Channel, Omari was glad to send them home. He wanted freedom for fast maneuver.

|

| Japanese cruiser Haguro |

He needed it. Halsey had the word on his sortie, and ComSoPac had lost no time in dispatching Rear Admiral Merrill’s task force to intercept the southbound Jap’s. When Merrill received this flash assignment his cruisers were off Vella Lavella, enjoying a breather after the strenuous bombardment work of the previous day. Commander B. L. (“Count”) Austin was on hand with DesDiv 46. Captain Arleigh Burke’s DesDiv 45 was refueling in Hathorn Sound at the entrance of Kula Gulf, but these destroyers topped off with dizzy speed, and by 2315 in the evening of November 1, Merrill’s force was racing headlong to meet the warships of Admiral Omari. |

| Light cruiser Sendai |

Omari did not expect to encounter a cruiser destroyer force. He expected, perhaps wishfully, to encounter a transport group. Bearing down on Empress Augusta Bay, he had his Imperial naval vessels disposed in a simple formation with heavy cruisers

Myoko (flagship) and

Haguro in the center; light cruiser

Sendai and destroyers

Shigure,

Samidare, and

Shiratsuyu to port; light cruiser

Agano and destroyers

Naganami, Hatsukaze, and

Wakatsuki to starboard.

|

| Agano off Sasebo, October 1942 |

Merrill’s force was disposed in line-of-bearing of unit guides. In column to starboard were Burke’s van destroyers:

Charles Ausburne (Commander L. K. Reynolds);

Dyson (Commander R. A. Gano);

Stanly (Commander R. W. Cavenagh); and

Claxton (Commander H. F. Stout). In center column steamed cruisers

Montpelier (flagship),

Cleveland, Columbia and

Denver. To port steamed Austin’s rear destroyers:

Spence (Commander H. J. Armstrong);

Thatcher (Commander L. R. Lampman);

Converse (Commander D. C. E. Hamberger); and

Foote (Commander Alston Ramsay).

|

| Burke in 1958 |

Omari’s force suffered the first blow when an American plane, detecting the Jap approach, planted a bomb in the superstructure of heavy cruiser

Haguro. That was at 0130 in the morning of November 2. Lamed by the hit,

Haguro reduced the formation’s speed to 30 knots. Then one of that cruiser’s planes reported Merrill’s task force coming up. The airmen erroneously notified Omari that one cruiser and three destroyers were in the offing. When, a few minutes later, he was informed by another air scout that a fleet of transports was unloading in Empress Augusta Bay, he sent his formation racing southeastward, hot for a massacre. Apparently the “transports” sighted were destroyer minelayers

Breese, Gamble, and

Sicard, at that time working along the coast under escort of destroyer

Renshaw.

|

USS Charles Ausburne (DD-570) in the vicinity

of the Solomon Islands, 23 March 1944 |

The night was black as carbon. Several of Omari’s warships carried radar apparatus, but he put more reliance on binoculars. American “Sugar George” radar was to out-see Japanese vision on this occasion. Merrill’s cruisers made the initial radar contact at 0227. He had already decided to maintain his ships in a position that would block the entrance to Empress Augusta Bay. Once action was joined, he intended to elbow the enemy westward, thereby gaining sea room which would enable him to fight a long-range gun battle with least chance of danger from Jap torpedoes. But his destroyers were to open proceedings with a torpedo attack, and the cruisers were to hold their fire until the “fish” had opportunity to strike the foe.

|

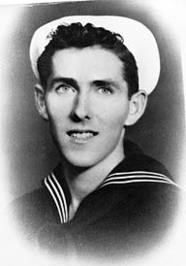

Reynolds, Luther Kendrick,

Commander, USN |

These plans were carefully laid, and they were known, chapter and verse, by Captain Arleigh Burke, leader of DesDiv 45. Commander Austin and DesDiv 46 were not so well versed in the detail. They were new to Task Force 39, and Austin was not thoroughly acquainted with Merrill’s battle techniques.

|

| USS Dyson (DD-572) at Sea 09-30-1944 |

As soon as radar contact was established, Merrill headed his formation due north. After a brief run, Burke’s van destroyers sliced away northwestward to deliver a torpedo strike as planned. Merrill then ordered a simultaneous turn to reverse course. Austin’s destroyers were instructed to countermarch, and then hit the enemy’s southern flank with torpedoes as soon as they could reach firing position.

|

Destroyer Squadron 23 officers of the squadron enjoy

a beer at "Cloob Des-Slot", Purvis Bay, Solomon Islands,

on 24 May 1944. Those present are (from left to right):

Commander R.A. Gano, Commanding Officer, USS Dyson (DD-572);

Commander Luther K. Reynolds, Commanding Officer, USS Charles Ausburne (DD-570);

Captain Arleigh A. Burke, Squadron Commodore;

Commander B.L. Austin, Commander Destroyer Division 46;

Commander D.C. Hamberger, Commanding Officer, USS Converse (DD-509);

Commander Herald Stout, Commanding Officer, USS Claxton (DD-571);

and Commander Henry J. Armstrong, Commanding Officer, USS Spence (DD-512). |

While Merrill’s cruisers were swinging around the hairpin turn, Burke’s destroyers were tacking in on Omari’s port side column. At 0246 Burke shouted the word over TBS, “My guppies are swimming!” But the Japs had sighted Merrill’s cruisers, and Omari was turning his formation southwestward. Because of this sudden turn, the barrage of 25 “guppies” sailed on into silence and oblivion, and Burke’s briskly executed attack failed to score.

Meanwhile, the Sendai column launched torpedoes at the American cruisers. But Merrill had not waited for this counterfire. When C.I.C. Informed him of Omari’s southwestward turn, he ordered his cruisers to let go with gunnery. I.J.N. Sendai was chief target for this booming fusillade. She caught a cataract of shells just as she was swinging to starboard, and the explosions blew her innards right out through the overhead.

|

Captain Arleigh A. Burke, USN, Commander Destroyer Squadron 23 (seated, right center)

with other officers of the squadron, during operations in the Solomon Islands, circa 1943.

Those present are (seated, left to right):

Commander Luther K. Reynolds, Commanding Officer, USS Charles Ausburne (DD-570);

Commander R.W. Cavenaugh; Captain Burke; and

Commander R.A. Gano, Commanding Officer, USS Dyson (DD-572).

(standing, left to right):

Commander Henry J. Armstrong, Commanding Officer, USS Spence (DD-512);

Lieutenant J.W. Bobb; Commander J.B. Morland; and Commander J.B. Calwell. |

Sendai’s abrupt come-uppance threw her column into a jumble. In the ensuing confusion, destroyers

Samidare and

Shiratsuyu collided full tilt, and went reeling off in precipitous retirement. That left the

Shigure all by herself, and she chased southward to join the Jap cruiser column.

Myoko and Haguro made a blind loop that tangled them up with the Agano column. Although Jap starshells had turned the night into a dazzle, the heavy cruisers failed to sight Merrill’s ships, and they maneuvered right into a tempest of American shellfire. Steaming in a daze, Myoko slammed into destroyer Hatsukaze and ripped off a section of that DD’s bow.

|

| USS Stanly |

Meantime, Burke’s “Little Beavers,” having launched torpedoes, became separated. And they did not get back into battle until 0349, when

Ausburne spotted

Sendai and hurried the vessel under with a volley of shots. Then

Samidare and

Shiratsuyu, the two DD’s which had collided, showed up on the radar screen. Burke took off after these departing enemies at top speed.

Commander Austin’s DesDiv 46 destroyers had run into hard luck. Destroyer

Foote misread Merrill’s signal to turn, and fell out of formation. While racing to rejoin Austin’s column, she was hit in the stern by a Jap torpedo which had been aimed at the American cruisers. Cruiser

Cleveland swerved just in time to miss the disabled DD by 100 yards. But destroyer

Spence, farther down the line, was not so lucky. Swinging hard right to give the cruiser column a clear line of fire, she sideswiped destroyer

Thatcher. The 30-knot brush sent sparks and sweat-beads flying, and removed a wide swath of paint, but both DD’s kept on traveling at high speed. Then at 0320 a Jap shell punctured

Spence’s hull at the waterline. Salt water got into a fuel tank, contaminating the oil, and this slow poison soon reduced the destroyers speed. As if this was not enough misfortune for one division, Austin’s DD’s lost a fine chance to strike at

Myoko and

Haguro with torpedoes. When his flagship sideswiped

Thatcher, Commander Austin dashed out on the bridge to see what was what. Some bright “pips” blossomed on the radar screen; Austin would have fired torpedoes at 4,000 yards or so, but the C.I.C. officer reported the targets were American. So the little scrape with

Thatcher cost something more than a paint job.

|

| USS Montpelier (CL-57) in Dec 1942 |

A moment later Spence made contact with cruiser Sendai. At that time the Jap vessel was a staggering merry-go-round, but her guns were still firing, and she was as dangerous as a wounded leopard. Austin maneuvered for torpedo fire, and Spence and Converse flung eight “fish” at the cripple. They did not sink her––Burke’s destroyers would presently perform that chore. Austin’s three DD’s raced on northwestward in an effort to catch Samidare and Shiratsuyu.

By 0352 Spence, Thatcher, and Converse had overhauled the two Jap DD’s and 19 American torpedoes were fanning out to catch each by the fantail. The 19 torpedoes scored a perfect zero. Some may have been improperly adjusted, but the zero probably had its source in improper fabrication.

|

| USS Cleveland (CL-55), underway at sea in late 1942. |

In counterattack,

Samidare and

Shiratsuyu flung shells and “fish” at Austin’s three destroyers. If the Jap “fish” missed, the marksmen at least had an excuse for poor torpedo work––the two Jap DD’s were dodging to escape a tempest of shell fire, and both ships had been badly damaged by collision.

Now Spence was running low on fuel, and what little she had was contaminated by salt water. Austin relinquished his tactical command to Thatcher’s skipper, Commander Lampman, and veered away with Spence to disengage. The maneuver brought his flag destroyer into line for a salvo from Arleigh Burke’s fast-shooting division. At 0425 a pack of projectiles slammed into the sea around Spence

|

| USS Columbia (CL-56), 15 May 1945 |

Over the TBS Commander Austin shouted a plea to Burke. WE’VE JUST HAD ANOTHER CLOSE MISS HOPE YOU ARE NOT SHOOTING AT US

Captain Burke’s answer was a classic of Navy humor. SORRY BUT YOU’LL HAVE TO EXCUSE THE NEXT FOUR SALVOS THEY’RE ALREADY ON THEIR WAY

Austin made haste to get Spence out of the vicinity. In dodging Burke’s ebullient fire, Spence picked up a good target in Jap destroyer Hatsukaze.

|

| USS Denver (CL-58) circa December 1942 |

Hatsukaze was the DD which

Myoko had rammed, and she was in no condition to dodge well-aimed salvos.

Spence closed the range to 4,000 yards while her gunners pumped shells into the disabled Jap.

Hatsukaze was soon flaming and wallowing, her engines dead. Austin yearned to finish off this foe, but

Spence’s ammunition was running low, so he put in a call for Burke’s destroyers to complete the execution. Thereupon an avalanche of 5-inchers from DesDiv 45 buried

Hatsukaze. About 0539 the ship rolled over and descended into the grave.

|

| USS Spence (DD-512) Date/Location unknown |

Spence joined up with DesDiv 45 as Burke ordered a retirement. Unable to catch

Samidare and

Shiratsuyu, destroyers

Thatcher and

Converse were also retiring. As day was making, Admiral Merrill had already headed his cruiser column eastward. While his DD’s were trying to tag fleeing Japs, Merrill’s cruisers had been maneuvering across the seascape in a duel with the Jap heavies. For over an hour the opposing formations had dodged about like gamecocks in a pit, neither side able to score a death dealing blow. Convinced that he had tangled with no less than seven heavy cruisers, Omari pulled out at 0337 and fled northwest up the coast of Bougainville. The American cruisers chased until daybreak, then Merrill turned back, anticipating aircraft from Rabaul.

|

USS Thatcher (DD-514), underway in

Boston harbor, Mass., 28 February 1943. |

Around 0500 Burke’s voice came cheerfully over the TBS. His destroyers were still to the west of Merrill’s cruisers, and he requested permission to pursue the fleeing Japs. According to Captain Briscoe, Merrill’s answer to this was, ARLIE THIS IS TIP FOR GODS SAKE COME HOME WE’RE LONESOMESo Burke came steaming south with his seven DD’s to keep the cruisers company.

“We were glad when those destroyers showed up,” another cruiser man recalled. “As we pulled away from Empress Augusta Bay the radar screen broke out in a rash of aerial pips. It looked like a blizzard coming down from Rabaul.”

|

USS Converse (DD-509) in San Francisco Bay,

9 October 1944. |

Destroyer

Foote, with her stern blown open, constituted a problem at this crisis.

Claxton was ordered to take the disabled ship in tow while

Ausburne and

Thatcher steamed as escorts. Vectored into position by a fighter-director team, 15 Allied aircraft flew to intercept the Jap planes racing down from the Bismarcks. Some 100 Jap carrier planes were too much for the Allied 15, and bulk of the defense fell upon Merrill’s weary gun crews.

About 0800 the Jap aircraft attacked the retiring ships. The formation roared right over damaged Foote, some ten miles astern of the cruisers. Lamed though she was, Foote put up an umbrella of flak. No bombs were dropped upon her, and she saw a plane plunge into the sea.

|

| USS Foote (DD-511) |

Five minutes later, the Jap birds swooped down on Merrill’s task force. He had the force disposed in a circular AA formation. As the bombers came over, he maneuvered to bring main batteries to bear, and the destroyers opened up with AA fire at about 14,000 yards. Merrill described it in his Action Report:

The scene was of an organized hell in which it was impossible to speak, hear, or even think. As the ships passed the first 90 degrees of their turn in excellent formation, the air seemed completely filled with bursting shrapnel and, to our great glee, enemy planes in a severe state of disrepair. . . . Planes were in flames as they passed over the flagship, exploding outside the destroyer screen. . . . Ten planes were counted in the water at one time, and seven additional were sent to crash well outside the formation.

|

A Japanese aircraft crashes (upper center) into the ocean

near the US cruiser Columbia on 2 November 1943,

during air attacks on Allied ships off Bougainville,

a few hours after the Naval Battle of Empress Augusta Bay. |

At the height of the battle, Merrill ordered a 360º turn which kept the warship carousel steaming clockwise. All the gunners seemed to be catching prizes from the air. Three Japs bailed out in parachutes and landed almost in the center of the wheeling formation. “Bettys” blew up in the sky and exploded in the water. Of the 70 or 80 planes which attacked, perhaps two dozen were shot down (Jap figures were never forthcoming). The Japs landed only two hits on cruiser

Montpelier, damaging a catapult and wounding one man. At 0812 they broke off the attack and ran northward, pursued by Allied fighter planes.

|

View forward from USS Columbia during the

Battle of Empress Augusta Bay. The ship visible ahead should be

USS Cleveland. |

The Battle of Empress Augusta Bay and its aerial epilogue were over. On the sea and in the air the enemy had taken a colossal thrashing. A light cruiser and a destroyer sunk, two destroyers disabled, heavy cruiser

Myoko dented by collision, heavy cruiser

Haguro severely damaged––Omari’s force slunk home in sorry defeat. In Merrill’s force destroyer

Foote was the one serious casualty, and even she would live to fight again. Cruiser

Denver and destroyer

Spence, with minor damage, would lose little time on the binnacle list.