--S.E. Smith

From: The United States Navy in World War II

Preface to Part II: Chapter 11: The Capture of U-505

By: Rear Admiral D. V. Gallery

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Class: Casablanca-Class Escort Carrier

Registry: CVE-60

Commissioned: 25, September 1943

| |

| Career (United States) | |

|---|---|

| Name: | USS Guadalcanal |

| Ordered: | 1942 |

| Builder: | Kaiser Shipyards |

| Laid down: | 5 January 1943 |

| Launched: | 5 June 1943 |

| Commissioned: | 25 September 1943 |

| Decommissioned: | 15 July 1946 |

| Struck: | 27 May 1958 |

| Motto: | Can do |

| Fate: | Sold for scrap on 30 April 1959 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class & type: | Casablanca-class escort carrier |

| Displacement: | 7,800 tons |

| Length: | 512 ft (156 m) overall |

| Beam: | 65 ft (20 m) |

| Draft: | 22 ft 6 in (6.86 m) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 19 knots (35 km/h) |

| Range: | 10,240 nmi (18,960 km) @ 15 kn (28 km/h) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: | 1 × 5 in/38 cal dual purpose gun, 16 × Bofors 40 mm guns (8x2), 20 × Oerlikon 20 mm cannons(20x1) |

| Aircraft carried: | 27 |

| Service record | |

| Part of: | Task Group 21.12 (1943-44) Task Group 22.3 (1944-45) Atlantic Reserve Fleet (1946-58) |

| Commanders: | Daniel V. Gallery |

| Operations: | Battle of the Atlantic |

| Victories: | U-544, U-515, U-68, U-505 (1944) |

| Awards: | Presidential Unit Citation, 3Battle stars |

USS Guadalcanal (CVE-60) was a Casablanca class escort carrier of the United States Navy. She was the first ship to carry her name.

She was converted from a Maritime Commission hull by Kaiser Co., Inc., of Vancouver, Washington. Originally Astrolabe Bay (AVG-60), she was reclassified ACV-60 on 20 August 1942 and launched as Guadalcanal(ACV-60) on 5 June 1943, sponsored by Mrs. Alvin I. Malstrom. She was reclassified CVE-60 on 15 July 1943; and commissioned at Astoria, Oregon on 25 September 1943, Captain Daniel V. Gallery in command. After shakedown training in which Capt. Gallery made the first take off and landing aboard his new ship, Guadalcanal performed pilot qualifications out of San Diego, California, and then departed on 15 November 1943, via the Panama Canal, for Norfolk, Va., arriving on 3 December. There she became flagship of Task Group 22.3 (TG 22.3), and with her escort destroyers set out from Norfolk on 5 January 1944 in search of enemy submarines in the North Atlantic.

First hunter-killer cruise[edit]

Earlier patrols by escort carriers had taught U-boats the danger of surfacing during daylight while aircraft were patrolling; but surfacing at night was safer because the escort carriers considered night flight operations too dangerous. The best the escort carriers could do was substitute extra fuel tanks for depth charges on a Grumman TBF Avenger, launch at sunset, and recover at dawn after the Avenger flew around all night.[1]

When Ultra intelligence revealed a planned U-boat refueling rendezvous 500 miles west of the Azores just before sunset on 16 January 1944,Guadalcanal stayed clear of the area until launching eight Avengers just before sunset to comb the rendezvous area. The Avengers found two U-boats engaged in refueling with another standing by, and dived out of the clouds to drop depth charges. All three submarines disappeared; but 32 survivors of U-544 were floating in a pool of oil. In their excitement to see the effects of their first successful attack, the Avenger pilots stayed aloft so long they returned to the carrier after sunset.[1]

Aircraft recoveries were slow because of bad approaches in the gathering dusk. After four landed successfully, the fifth Avenger landed too far right and put both wheels into the gallery walkway with its tail fouling the flight deck. The flight deck crew was unable to move the Avenger; and the three remaining planes were running out of fuel in total darkness. Guadalcanal turned on the lights and urged the pilots to try landing on the left side of the flight deck. The nervous pilots came in too high, too fast, and too far to port until one of them desperately cut power, bounced, and landed inverted in the water off the port side. The plane guard destroyer rescued the three crewmen from the unsuccessful landing and the crewmen from the two remaining planes which were instructed to ditch.[1]

No more night flying was attempted, and no more U-boats were discovered during daylight patrols. Gallery kept his flight deck crew busy training with the wrecked Avenger between flight operations. The Avenger was cabled to the ship so it wouldn't be lost; and the crew was timed with a stopwatch to see how long it took them to push it over the side. The plane would then be winched back aboard for another drill. After they could reliably clear the flight deck within four minutes; they were allowed to finally push the battered Avenger overboard with no cable attached.[1] After replenishing at Casablanca, the task group headed back for Norfolk and repairs, arriving on 16 February.

Second hunter-killer cruise[edit]

Departing again with her escorts on 7 March, Guadalcanal sailed with newly assigned air group VC-58 to Casablanca and got underway from that port on 30 March with a convoy bound for the United States. After three weeks of daylight flights finding no U-boats, Guadalcanal attempted night flight operations under the full moon of 8 April 1944. Four fully armed Avengers were launched just before sunset with recovery scheduled for 22:30. One of the Avengers found U-515recharging batteries on the surface northwest of Madeira, and forced the U-boat to submerge by dropping a stick of depth charges with U-515 silhouetted in a down-moon approach. Guadalcanal kept four Avengers aloft at all times through the night, and U-515 was repeatedly forced to submerge when attempting to surface to recharge batteries. Each sighting gave another fix on U-515's position; and Chatelain, Flaherty, Pillsbury and Pope detected the U-boat with SONAR at 07:00. The ships made coordinated attacks until U-515 was forced to the surface with depleted batteries and foul air at 14:00, andKapitaenleutenant Werner Henke scuttled his ship.[1]

Guadalcanal Avengers had detected a second U-boat about sixty miles away while holding down U-515; so they maintained patrols through the night of 9 April. U-68 was discovered at daybreak on 10 April recharging batteries on the surface 300 miles south of the Azores. Three Avengers attacked out of the dark western sky with depth charges and rocket fire. U-68 sank leaving three lookouts swimming in the wreckage, but only Hans Kastrup survived to be rescued when destroyers arrived an hour later.[1]

With the confidence gained through sinking two U-boats in the first two nights of flight operations, Guadalcanal continued night flight operations as the moon waned, and aircrew were well trained when the convoy arrived safely at Norfolk on 26 April 1944. Guadalcanal's success encouraged other carriers to practice might operations.[1]

Capture of U-505[edit]

After voyage repairs at Norfolk, Guadalcanal and her escorts departed Hampton Roads for sea again on 15 May 1944. Two weeks of cruising brought no contacts, and the task force decided to head for the coast of Africa to refuel. Ten minutes after reversing course, however, on 4 June 1944, 150 miles West of Cape Blanco in French West Africa, Chatelain detected U-505 as it was returning to its base in Brest, France after an 80-day commerce-destroying raid in the Gulf of Guinea. The destroyer loosed one depth charge attack and, guided in for a more accurate drop by circling TBF Avengers fromGuadalcanal, she soon made a second. This pattern blew relief valves all over the boat and cracked pipes in the engine room of the submarine, and rolled the U-boat on its beam ends. Shouts of panic from the engine room led Oberleutnant Harald Lange, making his first patrol as her captain, to believe his boat was mortally wounded. He blew his tanks and surfaced, barely 700 yards from the USS Chatelain in an attempt to save his crew. The destroyer fired a torpedo, which missed, and the surfaced submarine then came under the combined fire of the escorts and aircraft, forcing her crew to abandon ship.

Captain Gallery had been waiting and planning for such an opportunity, and having already trained and equipped his boarding parties, ordered Pillsbury's boat to make for the German sub and board her. Under the command of Lieutenant, junior grade Albert David, the party leaped onto the slowly circling submarine and found her abandoned. David and his men quickly captured all important papers, code books and the boat's Enigma machine while closing valves and stopping leaks. As Pillsbury attempted to get a tow-line on her the party managed to stop her engines. By this time a larger salvage group from Guadalcanal led by Commander Earl Trosino, Guadalcanal's Chief Engineer, arrived, and began the work of preparingU-505 to be towed. After securing the towline and picking up the German survivors from the sea, Guadalcanal started forBermuda with her priceless prize in tow. Abnaki rendezvoused with the task group and took over towing duties, the group arriving in Bermuda on 19 June after a 2,500-mile tow .Gallery later apologized to Trosino, a pre-war Merchant Marine chief engineer by training who had long since figured out the U-Boat's propulsion system, for not allowing him as prize captain to bring her in under her own power.[2]

U-505 was the first enemy warship captured on the high seas by the U.S. Navy since 1815. For their daring and skillful teamwork in this remarkable capture, Guadalcanal and her escorts shared in a Presidential Unit Citation. Lieutenant David received the Medal of Honor for leading the boarding party, and Captain Gallery received the Legion of Merit for conceiving the operation that led to U-505's capture. The captured submarine proved to be of inestimable value to American intelligence (for the remainder of the war she was operated by the U.S. Navy as the USS Nemo to learn the secrets of German U-boats), and its true fate was kept secret from the Germans until the end of the war. U-505 is the submarine exhibited in the Museum of Science and Industry (Chicago).

Arriving in Norfolk on 22 June 1944, Guadalcanal spent only a short time in port before setting out again on patrol. She departed Norfolk on 15 July and from then until 1 December, she made three anti-submarine cruises in the Western Atlantic. She sailed on 1 December for a training period in waters off Bermuda and Cuba that included refresher landings for pilots of her new squadron, gunnery practice, and anti-submarine warfare drills with Italian submarine R-9. Guadalcanalarrived Mayport, Fla., for carrier qualifications on 15 December and subsequently engaged in further training in Cuban water until 13 February 1945, when she arrived back in Norfolk. After another short training cruise to the Caribbean, she steamed into Mayport on 15 March for a tour of duty as carrier qualification ship, later moving to Pensacola, Florida for similar operations. After qualifying nearly 4,000 pilots, Guadalcanal returned to Norfolk, Va., and decommissioned there on 15 July 1946.

Guadalcanal entered the Atlantic Reserve Fleet at Norfolk and was redesignated CVU-60 on 15 July 1955, while still in reserve. She was finally stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 27 May 1958 and she was sold for scrap to the Hugo Neu Corp. of New York on 30 April 1959. She was in the process of being towed to Japan for scrapping, when Capt. Gallery also made the very last landing and take off from the ship, using a helicopter, off Guantanamo, Cuba.

Awards[edit]

Guadalcanal was awarded three battle stars and a Presidential Unit Citation for service in World War II. Her Presidential Unit Citation was personally ordered by Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations.[3]

Class: Type IXc U-Boat

Commissioned: 26, August 1941

U-505 shortly after being captured | |

| Career (Nazi Germany) | |

|---|---|

| Name: | U-505 |

| Ordered: | 25 September 1939[1] |

| Builder: | Deutsche Werft AG, Hamburg |

| Yard number: | 295[1] |

| Laid down: | 12 June 1940[1] |

| Launched: | 24 May 1941[1] |

| Commissioned: | 26 August 1941[1] |

| Fate: | Captured on 4 June 1944 by US Navy ships in the south Atlantic.[2][3] |

| Status: | Preserved as a museum ship[2][3] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Type IXC submarine |

| Displacement: | 1,120 t (1,100 long tons) surfaced 1,232 t (1,213 long tons) submerged |

| Length: | 76.8 m (252 ft 0 in) overall 58.7 m (192 ft 7 in) pressure hull |

| Beam: | 6.8 m (22 ft 4 in) overall 4.4 m (14 ft 5 in) pressure hull |

| Height: | 9.4 m (30 ft 10 in) |

| Draft: | 4.7 m (15 ft 5 in) |

| Propulsion: | 2 MAN M9V40/46 supercharged 9-cylinder diesel engines, 4,000 hp (3,000 kW) 2 SSW GU345/34 double-acting electric motors, 1,000 hp (750 kW) |

| Speed: | 18.2 knots (33.7 km/h) surfaced 7.3 knots (13.5 km/h) submerged |

| Range: | 24,880 nmi (46,080 km; 28,630 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h) surfaced 117 nautical miles (217 km; 135 mi) at 4 kn (7.4 km/h) submerged |

| Test depth: | 230 m (750 ft) |

| Complement: | 48 to 56 |

| Armament: | 6 torpedo tubes (four bow, two stern) 22 55 cm (22 in) torpedoes 1 10.5 cm SK C/32 naval gun[4](110 rounds) |

| Service record | |

| Part of: | Kriegsmarine 4th U-boat Flotilla (Training) 26 August 1941 – January 1942 2nd U-boat Flotilla (Front Boat, 12 patrols) 1 February 1942 – 4 June 1944 |

| Identification codes: | M 46 074 |

| Commanders: | KrvKpt. Axel-Olaf Loewe (26 August 1941 – 5 September 1942) Kptlt. Peter Zschech (6 September 1942 – 24 October 1943) Oblt.z.S.. Paul Meyer (acting) (24 October – 7 November 1943) Oblt.z.S.. Harald Lange (8 November 1943 – 4 June 1944) |

| Operations: | 12 patrols |

| Victories: | Eight ships sunk for a total of 44,962 gross register tons (GRT) |

U-505 (IXC U-Boat)

| |

| Coordinates | 41°47′30″N 87°34′53″W |

| Built | 1941 |

| Architect | Deutsches Werft Shipyard, Hamburg, Germany |

| Governing body | Private |

| NRHP Reference # | 89001231 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | 1989[5] |

| Designated NHL | 1989[6] |

U-505 is a German Type IXC U-boat built for service in theKriegsmarine during World War II. She was captured on 4 June 1944 byUnited States Navy Task Group 22.3 (TG 22.3). Her codebooks,Enigma machine and other secret materials found on board assisted Allied code breaking operations.[7]

All but one of U-505's crew were rescued by the Navy task group. The submarine was towed to Bermuda in secret and her crew was interned at a US prisoner of war camp where they were denied access toInternational Red Cross visits. The Navy classified the capture as top secret and prevented its discovery by the Germans.

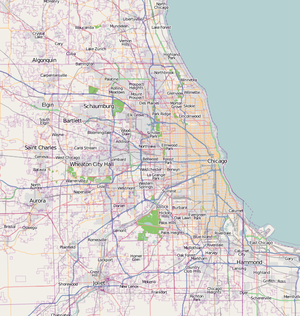

In 1954, U-505 was donated to the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, Illinois and is now a museum ship.

She is one of six U-boats that were captured by Allied forces during World War II, and the first warship to be captured by U.S. forces on the high seas since the War of 1812. In her uniquely unlucky career with theKriegsmarine, she also had the distinction of being the "most heavily damaged U-boat to successfully return to port" in World War II (on her fourth patrol) and the only submarine in which a commanding officertook his own life in combat conditions (on her tenth patrol, following six botched patrols).[8] U-505 is one of four German World War II U-boats that survive as museum ships, and one of two Type IXCs still in existence, the other being U-534.

Anti-sub task force[edit]

Ultra intelligence from decrypted German cipher messages had informed the Allies that U-boats were operating near Cape Verde, but had not revealed their exact locations.[23][24] The U.S. Navy dispatched Task Group 22.3, a "Hunter-Killer" group, commanded by Captain Daniel V. Gallery, USN, to the area. TG 22.3 consisted of Gallery's escort aircraft carrierGuadalcanal, and five destroyer escorts under Commander Frederick S. Hall: Pillsbury, Pope, Flaherty, Chatelain, andJenks.[25] On 15 May 1944, TG 22.3 sailed from Norfolk, Virginia. Starting in late May, the task group began searching for U-boats in the area, using high-frequency direction-finding fixes ("Huff-Duff") and air and surface reconnaissance.

Detection and attack[edit]

At 11:09 on 4 June 1944, TG 22.3 made sonar (ASDIC) contact with U-505 at 21°30′N 19°20′W, about 150 nautical miles (278 km; 173 mi) off the coast of Río de Oro.[23] The sonar contact was only 800 yards (700 m) away off Chatelain's starboard bow. The escorts immediately moved towards the contact, while Guadalcanal moved away at top speed and launched an F4F Wildcat fighter to join another Wildcat and a TBM Avenger which were already airborne.[26]

Chatelain was so close to U-505 that depth charges would not sink fast enough to intercept the U-boat,[citation needed] so instead she fired Hedgehogs before passing the submarine and turning to make a follow-up attack with depth charges.[23]At around this time, one of the aircraft sighted U-505 and fired into the water to mark the position while Chatelain dropped depth charges. Immediately after the detonation of the charges a large oil slick spread on the water and the fighter pilot overhead radioed, "You struck oil! Sub is surfacing!"[27] Less than seven minutes after Chatelain's first attack began, the badly damaged U-505 surfaced less than 600 metres (700 yd) away.[26] Chatelain immediately commenced fire on U-505with all available automatic weapons, joined by other ships of the task force as well as the two Wildcats.[23]

Believing U-505 to be seriously damaged, Oblt.z.S.. Lange ordered his crew to abandon ship. This order was obeyed so promptly that scuttling was not completed, (although some valves were opened) and the engines were left running.[23] With the engines still functioning and the rudder damaged by depth charges, U-505 circled clockwise at approximately 7 knots (13 km/h). Seeing the U-boat turning toward him and believing she was preparing to attack, the commanding officer ofChatelain ordered a single torpedo to be fired at the submarine; the torpedo missed, passing ahead of the now-abandonedU-505.[23]

Salvage operations[edit]

While Chatelain and Jenks collected survivors, an eight-man party from Pillsbury led by Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Albert David came alongside U-505 in a boat and entered via the conning tower. There was a dead man on the deck (the only fatality of the action), but U-505 was otherwise deserted. The boarding party secured charts and codebooks, closed scuttling valves and disarmed demolition charges. They stopped the water coming in, and although low in the water and down by the stern,U-505 remained afloat. They also stopped her engines.[23]

While the boarding party secured U-505, Pillsbury attempted to take her in tow, but collided repeatedly with her and had to move away with three compartments flooded. Instead, a second boarding party fromGuadalcanal rigged a towline from the aircraft carrier to the U-boat.[23]

Commander Earl Trosino (Guadalcanal's chief engineer), joined the salvage party. He disconnected U-505's diesels from her electric driving motors, while leaving these motors clutched to the propeller shafts. With the U-boat moving under tow byGuadalcanal, the propellers "windmilled" as they passed through the water, turning the shafts and the drive motors. The motors acted as electrical generators, and charged U-505's batteries. With power from the batteries, U-505's pumps cleared out the water let in by the attempted scuttling, and her air compressors blew out the ballast tanks, bringing her up to full surface trim.[23]

After three days of towing, Guadalcanal transferred U-505 to the fleet tug Abnaki. On Monday, 19 June, U-505 entered Port Royal Bay, Bermuda, after a tow of 1,700 nautical miles (3,150 km; 1,960 mi).

This action was the first time the U.S. Navy had captured an enemy vessel at sea since the War of 1812. 58 prisoners were taken from U-505, three of them wounded (including Lange); only one of the crew was killed in the action.

U-505's crew was interned at Camp Ruston, near Ruston, Louisiana. Among the guards were members of the U.S. Navy baseball team, composed mostly of minor league professional baseball players who had previously toured combat areas to entertain the troops. The players taught some of the U-505 sailors to play the game.[28]

Outcome[edit]

The cipher materials captured on U-505 included the special "coordinate" code, the regular and officer Enigma settings for June 1944, the current short weather codebook, the short signal codebook and bigram tables due to come into effect in July and August respectively.

The material from U-505 arrived at the decryption establishment at Bletchley Park on 20 June 1944. While the Allies were able to break most Enigma settings by intense cryptanalysis (including heavy use of the electromechanical "bombes"), having the Enigma settings for the U-boats saved a lot of work and time, which could be applied to other keys. The settings break was only valid until the end of June and therefore had an extremely limited outcome on the eventual cracking of the enigma code, but having the weather and short signal codebooks and bigram tables made the work easier.

The "coordinate" code was used in German messages as an added layer of security for locations. Allied commanders sent Hunter-Killer task groups to these known U-boat locations, and routed shipping away.[29]

A more lasting benefit came from the intact capture of the U-boat's two G7es (Zaunkönig T-5) acoustic homing torpedoes. These were thoroughly analyzed and then tested on the range, giving information that was invaluable in improving theFoxer and FXR countermeasures systems, as well as the doctrine for using them to protect escorts.[30]

That U-505 was captured and towed—rather than merely sunk after the codebooks had been taken—was considered to have endangered the Ultra secret. The U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral King, considered court-martialling Captain Gallery.[29] To protect the secret, U-505's crewmen, who knew of the U-boat's capture, were isolated from other prisoners of war; the Red Cross were denied access to them. Ultimately, the Kriegsmarine declared the crew dead and informed the families to that effect. The last of the German crew was not returned until 1947.[31]

For leading the boarding party, LTJG Albert David received the Medal of Honor, the only time it was awarded to an Atlantic Fleet sailor in World War II. Torpedoman's Mate Third Class Arthur W. Knispel and Radioman Second Class Stanley E. Wdowiak, the first two to follow David into the submarine, received the Navy Cross. Seaman First Class Earnest James Beaver, also of the boarding party, received the Silver Star. Commander Trosino received the Legion of Merit. Captain Gallery, who had conceived and executed the operation, received the Navy Distinguished Service Medal.

The Task Group was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation. Admiral Royal E. Ingersoll, Commander in Chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, cited the Task Group for "outstanding performance during anti-submarine operations in the eastern Atlantic on 4 June 1944, when the Task Group attacked, boarded, and captured the German submarine U-505 ... The Task Group's brilliant achievement in disabling, capturing, and towing to a United States base a modern enemy man-of-war taken in combat on the high seas is a feat unprecedented in individual and group bravery, execution, and accomplishment in the Naval History of the United States."[23]

U-505 was kept at the navy base in Bermuda and intensively studied by U.S. Navy intelligence and engineering officers. Some of what was learned was included in postwar diesel submarine designs. To maintain the illusion that she had been sunk rather than captured, she was temporarily renamed USS Nemo.[32]

Museum ship[edit]

After the war, the Navy had no further use for U-505. She had been thoroughly examined in Bermuda, and was now moored derelict at the Portsmouth Navy Yard. It was decided to use her as a target for gunnery and torpedo practice until she sank.[23] In 1946, Gallery, now a rear admiral, told his brother Father John Gallery about this plan. Father John contacted President Lenox Lohr of Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry (MSI) to see if they would be interested in U-505. MSI, established by Chicago businessman Julius Rosenwald, was a center for "industrial enlightenment" and public science education, specializing in interactive exhibits. As the museum already planned to display a submarine, the acquisition of U-505seemed ideal.[23] In September 1954, U-505 was donated to Chicago by the U.S. government, a public subscription among Chicago residents raised $250,000 for transporting and installing the boat. The vessel was towed by United States Coast Guard tugs and cutters through the Great Lakes, making a stop in Detroit, Michigan in the summer of 1954.[33] On 25 September 1954, U-505 was dedicated as a permanent exhibit and a war memorial to all the sailors who lost their lives in the two Battles of the Atlantic.

When U-505 was donated to the Museum, she had been sitting neglected at the Portsmouth Navy Yard for nearly ten years; just about every removable part had been stripped from her interior. She was in no condition to serve as an exhibit.

Admiral Gallery proposed a possible solution. At his suggestion, Lohr contacted the German manufacturers who had supplied U-505's original components and parts, asking for replacements. As the Admiral reported in his autobiography, Eight Bells and All's Well, to his and the museum's surprise, every company supplied the requested parts without charge. Most included letters that said in effect, "We are sorry that you have our U-boat, but since she's going to be there for many years, we want her to be a credit to German technology."[34]

In 1989, U-505 was designated a National Historic Landmark. When the U.S. Navy demolished its Arctic Submarine Laboratory in Point Loma, California in 2003, U-505's original observation periscope was discovered. Before the submarine was donated to the MSI, the periscope had been removed from U-505 and placed in a water tank used for research. After being recovered, the periscope was given to the museum to be displayed along with the submarine.[35][36]

By 2004, the U-boat's exterior had suffered noticeable damage from the weather; so in April 2004, the museum moved the U-boat to a new underground, covered, climate-controlled location. Now protected from the elements, the restored U-505reopened to the public on 5 June 2005.

| Daniel V. Gallery | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 10, 1901 Chicago, Illinois |

| Died | January 16, 1977 (aged 75) Bethesda, Maryland |

| Buried at | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service | 1917–1960 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | U.S. Navy Fleet Air Base, Reykjavik, Iceland USS Guadalcanal USS Hancock Tenth Naval District |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Navy Distinguished Service Medal Bronze Star |

| Relations | Brothers: Philip D. Gallery, Rear Admiral, USNA, World War II, Decorated Destroyer Commander; William O. Gallery, Rear Admiral, USNA, Naval Aviator, World War II, DFC; John I. Gallery, Catholic Priest and, during World War II, Navy Chaplain; an elder brother died in childhood. Sisters: Margaret Gallery; Marcia Gallery, d. age 17. |

Rear Admiral Daniel Vincent Gallery (July 10, 1901 – January 16, 1977) was an officer in the United States Navy who saw extensive action during World War II. He fought in the Battle of the Atlantic, his most notable achievement was the capture of the German submarineU-505 on June 4, 1944. In the post-war era, he was a leading player in the so-called "Revolt of the Admirals" – the dispute between the Navy and the Air Force over whether the U.S. Armed Forces should emphasize aircraft carriers or strategic bombers. Gallery was also a prolific author of both fiction and non-fiction.

In 1942, Gallery took command of the Fleet Air Base in Reykjavík, Iceland, where he was awarded the Bronze Star for his actions against German submarines. It was there that he first conceived his plan to capture a U-boat.

In 1943, Gallery was appointed commander of the escort carrier USS Guadalcanal, which he commissioned. In January 1944 he commanded antisubmarine Task Group 21.12 (TG 21.12) out of Norfolk, Virginia, with Guadalcanal as the flagship. TG 21.12 sank the German submarine U-544.[3]

In March 1944 Task Group 22.3 was formed with Guadalcanal as the flagship. On this cruise Gallery pioneered 24-hour flight operations from escort carriers (by this time, U-boats were remaining submerged during daylight to avoid carrier-based aircraft). On April 9, the task group sank U-515 (commanded by the U-boat ace Kapitänleutnant Werner Henke). After a long battle the submarine was forced to the surface among the attacking ships and the surviving crew abandoned ship. The deserted U-515 was hammered by rockets and gunfire before she finally sank. Captain Gallery saw that this would have been a perfect opportunity to capture the vessel. He decided to be ready the next time such an opportunity presented itself. The next night aircraft from the task group caught U-68 on the surface, in broad moonlight, and sank her with one survivor, a lookout caught on-deck when the U-boat crash dived.

On the next cruise of TG 22.3, Captain Gallery took the unusual step of forming boarding parties, in case of another chance to capture a U-boat arose. On June 4, 1944, the task group crossed paths with U-505 off the coast of Africa.[4] U-505 was spotted running on the surface by two F4F Wildcat fighters from Guadalcanal. Her captain, Oberleutnant Harald Lange, dived the boat to avoid the fighters. But they could see the submerged submarine and vectored destroyers onto her track. The experienced antisubmarine warfare team laid down patterns of depth charges that shook U-505 up badly, popping relief valves and breaking gaskets, resulting in water sprays in her engine room. Based on reports from the engine room, the captain believed his boat to be heavily damaged and ordered the crew to abandon ship, which was done so hastily that full scuttling measures were not completed.

Captain Gallery's boarding party from the destroyer escort USS Pillsbury was ordered to board the foundering submarine and if possible capture her. The destroyers in range used their .50 caliber and 20 mm antiaircraft guns to chase the Germans off the vessel so the boarding party could get onto her. They replaced the cover of the sea strainer, thus keeping the U-boat from sinking immediately. The boarders retrieved the submarine's Enigma coding machine and current code books. (This was a primary goal of the mission because it would enable the codebreakers in Tenth Fleet to read German signals immediately, without having to break the codes first). They got her under control, making U-505 the first foreign man-of-war captured in battle on the high seas by the U.S. Navy since the War of 1812.

This incident was the last time that the order "Away All Boarders!" was given by a U.S. Navy captain. Lieutenant Albert David, who led the boarding party, received the Medal of Honor for his courage in boarding a foundering submarine that presumably had scuttling charges set to explode – the only Medal of Honor awarded in the Atlantic Fleet during World War II. Task Group 22.3 was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation and Captain Gallery received the Distinguished Service Medal for capturingU-505.

He also received a blistering dressing-down from Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations.[5] King pointed out that unless U-505's capture could be kept an absolute secret, the Germans would change their codes and change out the cipher wheels in the Enigma. Gallery managed to impress his crews with the vital importance of maintaining silence on the best sea story any of them would ever see. His success made the difference between his getting a medal or getting a court-martial. (It is interesting that two noted naval historians, Samuel Eliot Morison and Clay Blair, Jr. are on opposite sides of Gallery's case.) After the war, Admiral King personally approved the award of the Presidential Unit Citation to Task Group 22.3 for the capture of the U-boat.[6]

Toward the end of World War II Captain Gallery was given command of the aircraft carrier USS Hancock.

No comments:

Post a Comment