I stepped aboard PT-41. "You may cast off, Buck," I said, "when you are ready."

Although the flotilla consisted of only four battle-scarred PT boats, its size was no gauge of the uniqueness of its mission. This was the desperate attempt by a commander-in-chief and his key staff to move thousands of miles through the enemy's lines to another war theatre, to direct a new and intensified assault. Nor did the Japanese themselves underestimate the significance of such a movement. "Tokyo Rose" had announced gleefully that, if captured, I would be publicly hanged on the Imperial Plaza in Tokyo, where the Imperial towers overlooked the traditional parade ground of the Emperor's Guard divisions. Little did I dream that bleak night that five years later, at the first parade review of Occupation troops, I would take the salute as supreme commander for the Allied Powers on the precise spot so dramatically predicted for my execution.

The tiny convoy rendezvoused at Turning Buoy just outside the minefield at 20:00. Then we roared through in single file, Bulkeley leading and Admiral Rockwell in PT-34 closing the formation.

On the run to Cabra Island, many white lights were sighted--the enemy's signal that a break was being attempted through the blockade. The noise of our engines had been heard, but the sound of a PT engine is hard to differentiate from that of a bomber, and they evidently mistook it. Several boats passed. The sea rose and it began to get rough. Spiteful waves slapped and snapped at the thin skin of the little boats; visibility was becoming poorer.

As we began closing on the Japanese blockading fleet, the suspense grew tense. Suddenly, there they were, sinister outlines against the curiously peaceful formations of lazily drifting cloud. We waited, hardly breathing, for the first burst of shell that would summon us to identify ourselves. Ten seconds. Twenty. A full minute. No gun spoke; the PT's rode so low in the choppy seas that they had not spotted us.

Bulkeley changed at once to a course that brought us to the west and north of the enemy craft, and we slid by in the darkness. Again and again, this was to be repeated during the night, but our luck held.

The weather deteriorated steadily, and towering waves buffeted our tiny, war weary, blacked-out vessels. The flying spray drove against our skin like stinging pellets of birdshot. We would fall off into a trough, then climb up the near slope of a steep water peak, only to slide down the other side. The boat would toss crazily back and forth, seeming to hang free in space as though about to breach, and then would break away and go forward with a rush. I recall describing the experience afterward as what it must be like to take a trip in a concrete mixer. The four PT's could no longer keep formation, and by 03:30 the convoy had scattered. Bulkeley tried for several hours to collect the others, but without success. Now each skipper was on his own, his rendezvous just off the uninhabited Cuyo Island.

It was a bad night for everybody. At dawn, Lieutenant (j.g.) V. E. Schumacher, commander of PT-32, saw what he took for a Jap destroyer bearing down at 30 knots through the early morning fog. The torpedo tubes were instantly cleared for action, and the 600-gallon gasoline drums jettisoned to lighten the vessel when teh time came to make a run for it. Just before the signal to fire, the onrushing "enemy" was seen to be the PT-41--mine.

The first boat to arrive at Tagauayan at 09:30 on the morning of 12, March was PT-34 under the command of Lieutenant R.G. Kelly. PT-32 and Bulkeley's PT-41 arrived at approximately 16:00 with PT-32 running out of fuel; those aboard were placed on the two other already crowded craft. A submarine which had been ordered to join us at the Cuyos did not appear. We waited as the day's stifling heat intensified, still spots on the water camouflaged as well as possible from the prying eyes of searching enemy airmen. Hours passed and at last we could wait no longer for Ensign A. B. Akers' PT-35 (it arrived two hours after we left). I gave the order to move out southward into the Mindanao Sea for Cagayan, on the northern coast. This time Rockwell's boat led and PT-41 followed. The night was clear, the sea rough and high.

Once more, huge and hostile, a Japanese warship loomed dead ahead through the dark. We were too near to run, too late to dodge. Instantly we cut engines, cleared for action--and waited. Seconds ticked into minutes, but no signals flashed from the battleship as she steamed slowly westward across our path. If we had been seen at all, we had ben mistaken far part of the native fishing fleet. Our road to safety was open.

We made it into Cagayan at 07:00 on Friday, 13 March. I called together the officers and men of both PT's. "It was done in true naval style," I told them. "It gives me great pleasure and honor to award the boats' crews the Silver Star for gallantry for fortitude in the face of heavy odds."

--General of the Army, Douglas MacArthur

From: The United States Navy in World War II

Chapter 10: Retreat

Compiled and Edited by: S.E. Smith

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Douglas MacArthur

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

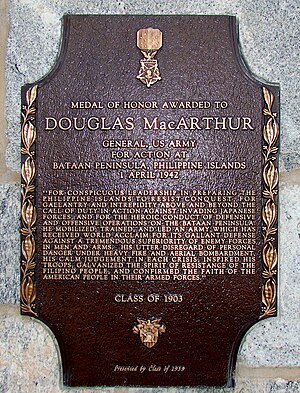

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur (26 January 1880 – 5 April 1964) was an American general and field marshal of the Philippine Army who was Chief of Staff of the United States Army during the 1930s and played a prominent role in the Pacific theater during World War II. He received the Medal of Honor for his service in thePhilippines Campaign, which made him and his father Arthur MacArthur, Jr., the first father and son to be awarded the medal. He was one of only five men ever to rise to the rank of General of the Army in the U.S. Army, and the only man ever to become a field marshal in the Philippine Army.

Raised in a military family in the American Old West, MacArthur wasvaledictorian at the West Texas Military Academy, and First Captainat the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he graduated top of the class of 1903. During the 1914 United States occupation of Veracruz, he conducted a reconnaissance mission, for which he was nominated for the Medal of Honor. In 1917, he was promoted from major to colonel and became chief of staff of the 42nd (Rainbow) Division. In the fighting on the Western Front during World War I, he rose to the rank of brigadier general, was again nominated for a Medal of Honor, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross twice and the Silver Star seven times.

Philippines Campaign (1941–42)

On 26 July 1941, Roosevelt federalized the Philippine Army, recalled MacArthur to active duty in the U.S. Army as a major general, and named him commander of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). MacArthur was promoted to lieutenant general the following day,[113] and then to general on 20 December. At the same time, Sutherland was promoted to major general, while Marshall, Spencer B. Akin, and Hugh J. Casey were all promoted to brigadier general.[114] On 31 July 1941, the Philippine Department had 22,000 troops assigned, 12,000 of whom were Philippine Scouts. The main component was the Philippine Division, under the command of Major General Jonathan M. Wainwright.[115]

Between July and December 1941, the garrison received 8,500 reinforcements.[116] After years of parsimony, much equipment was shipped. By November, a backlog of 1,100,000 shipping tons of equipment intended for the Philippines had accumulated in U.S. ports and depots awaiting vessels.[117] In addition, the Navy intercept station in the islands, known as Station CAST, had an ultra secret Purple cipher machine, which decrypted Japanese diplomatic messages, and partial codebooks for the latest JN-25 naval code. Cast sent MacArthur its entire output, via Sutherland, the only officer on his staff authorized to see it.[118]

At 03:30 local time on 8 December 1941 (about 09:00 on 7 December in Hawaii),[119] Sutherland learned of the attack on Pearl Harborand informed MacArthur. At 05:30, the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, General George Marshall, ordered MacArthur to execute the existing war plan, Rainbow Five. MacArthur did nothing. On three occasions, the commander of the Far East Air Force, Major GeneralLewis H. Brereton, requested permission to attack Japanese bases in Formosa, in accordance with prewar intentions, but was denied by Sutherland. Not until 11:00 did Brereton speak with MacArthur about it, and obtained permission.[120] MacArthur later denied having the conversation.[121] At 12:30, aircraft of Japan's 11th Air Fleet achieved complete tactical surprise when they attacked Clark Fieldand the nearby fighter base at Iba Field, and destroyed or disabled 18 of Far East Air Force's 35 B-17s, 53 of its 107 P-40s, three P-35s, and more than 25 other aircraft. Most were destroyed on the ground. Substantial damage was done to the bases, and casualties totaled 80 killed and 150 wounded.[122] What was left of the Far East Air Force was all but destroyed over the next few days.[123]

Prewar defense plans assumed the Japanese could not be prevented from landing on Luzon and called for U.S. and Filipino forces to abandon Manila and retreat with their supplies to the Bataan peninsula. MacArthur attempted to slow the Japanese advance with an initial defense against the Japanese landings. However, he reconsidered his confidence in the ability of his Filipino troops after the Japanese landing force made a rapid advance after landing atLingayen Gulf on 21 December,[124] and ordered a retreat to Bataan.[125]Manila was declared an open city at midnight on 24 December, without any consultation with Admiral Thomas C. Hart, commanding the Asiatic Fleet, forcing the Navy to destroy considerable amounts of valuable material.[126]

On the evening of 24 December, MacArthur moved his headquarters to the island fortress of Corregidor in Manila Bay, boarding the Army transport Don Esteban after 19:00 arriving Corregidor at 21:30, with his headquarters reporting to Washington as being open on the 25th.[127][128] A series of air raids by the Japanese destroyed all the exposed structures on the island and USAFFE headquarters was moved into the Malinta Tunnel. Later, most of the headquarters moved to Bataan, leaving only the nucleus with MacArthur.[129]The troops on Bataan knew that they had been written off but continued to fight. Some blamed Roosevelt and MacArthur for their predicament. A ballad sung to the tune of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" called him "Dugout Doug".[130] However, most clung to the belief that somehow MacArthur "would reach down and pull something out of his hat."[131]

On 1 January 1942, MacArthur accepted $500,000 from President Quezon of the Philippines as payment for his pre-war service. MacArthur's staff members also received payments: $75,000 for Sutherland, $45,000 for Richard Marshall, and $20,000 for Huff.[132][133] Eisenhower—after being appointed Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force (AEF)—was also offered money by Quezon, but declined.[134] These payments were known only to a few in Manila and Washington, including President Roosevelt and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, until they were made public by historian Carol Petillo in 1979. The revelation tarnished MacArthur's reputation.[135]

Escape to Australia and Medal of Honor

Main article: Douglas MacArthur's escape from the Philippines

In February 1942, as Japanese forces tightened their grip on the Philippines, MacArthur was ordered by President Roosevelt to relocate to Australia.[136] On the night of 12 March 1942, MacArthur and a select group that included his wife Jean and son Arthur, as well as Sutherland, Akin, Casey, Richard Marshall, Charles A. Willoughby, LeGrande A. Diller, and Harold H. George, left Corregidor in four PT boats. MacArthur, his family and Sutherland traveled aboard PT 41, commanded by Lieutenant John D. Bulkeley. The others followed aboard PT 34, PT 35 and PT 32. MacArthur and his party reached Del Monte Airfield on Mindanao, where B-17s picked them up, and flew them to Australia.[137][138] His famous speech, in which he said, "I came through and I shall return", was first made at Terowie, a small town in South Australia, on 20 March.[139] Washington asked MacArthur to amend his promise to "We shall return". He ignored the request.[140]

Bataan surrendered on 9 April,[141] and Corregidor on 6 May.[142] George Marshall decided that MacArthur would be awarded the Medal of Honor, a decoration for which he had twice previously been nominated, "to offset any propaganda by the enemy directed at his leaving his command".[143]Eisenhower pointed out that MacArthur had not actually performed any acts of valor as required by law, but Marshall cited the 1927 award of the medal toCharles Lindbergh as a precedent. Special legislation had been passed to authorize Lindbergh's medal, but while similar legislation was introduced authorizing the medal for MacArthur by Congressmen J. Parnell Thomas andJames E. Van Zandt, Marshall felt strongly that a serving general should receive the medal from the President and the War Department.[144] MacArthur chose to accept it on the basis that "this award was intended not so much for me personally as it is a recognition of the indomitable courage of the gallant army which it was my honor to command."[145] Arthur and Douglas MacArthur thus became the first father and son to be awarded the Medal of Honor. They remained the only pair until 2001, when Theodore Roosevelt was awarded posthumously for his service during the Spanish American War, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.having received one posthumously for his service during World War II.[146][147] His citation, written by George Marshall,[148] read:

For conspicuous leadership in preparing the Philippine Islands to resist conquest, for gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty in action against invading Japanese forces, and for the heroic conduct of defensive and offensive operations on the Bataan Peninsula. He mobilized, trained, and led an army which has received world acclaim for its gallant defense against a tremendous superiority of enemy forces in men and arms. His utter disregard of personal danger under heavy fire and aerial bombardment, his calm judgment in each crisis, inspired his troops, galvanized the spirit of resistance of the Filipino people, and confirmed the faith of the American people in their Armed Forces.[149]

As the symbol of the forces resisting the Japanese, MacArthur received many other accolades. The Native American tribes of the Southwest chose him as a "Chief of Chiefs", which he acknowledged as from "my oldest friends, the companions of my boyhood days on the Western frontier".[150] He was touched when he was named Father of the Year for 1942, and wrote to the National Father's Day Committee that:

By profession I am a soldier and take pride in that fact, but I am prouder, infinitely prouder to be a father. A soldier destroys in order to build; the father only builds, never destroys. The one has the potentialities of death; the other embodies creation and life. And while the hordes of death are mighty, the battalions of life are mightier still. It is my hope that my son when I am gone will remember me, not from battle, but in the home, repeating with him our simple daily prayer, "Our father, Who art in Heaven."[150]

For conspicuous leadership in preparing the Philippine Islands to resist conquest, for gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty in action against invading Japanese forces, and for the heroic conduct of defensive and offensive operations on the Bataan Peninsula. He mobilized, trained, and led an army which has received world acclaim for its gallant defense against a tremendous superiority of enemy forces in men and arms. His utter disregard of personal danger under heavy fire and aerial bombardment, his calm judgment in each crisis, inspired his troops, galvanized the spirit of resistance of the Filipino people, and confirmed the faith of the American people in their Armed Forces.[149]

By profession I am a soldier and take pride in that fact, but I am prouder, infinitely prouder to be a father. A soldier destroys in order to build; the father only builds, never destroys. The one has the potentialities of death; the other embodies creation and life. And while the hordes of death are mighty, the battalions of life are mightier still. It is my hope that my son when I am gone will remember me, not from battle, but in the home, repeating with him our simple daily prayer, "Our father, Who art in Heaven."[150]

No comments:

Post a Comment